Lesser Known Facts About Learning & How to get Better at Studying

25 May 2020After a year of self-studying machine learning full time using nothing but online resources, I thought I’d share some insights about learning. This is a topic I have spent a lot of time researching throughout my journey of changing careers to machine learning (my background is in business/marketing).

The following is mostly based on my experience applying lessons from two books – A mind for numbers, and Pragmatic Thinking and Learning.

When reading books about learning, it’s easy to become overwhelmed with the flurry of techniques they throw at you. It’s nearly impossible to successfully apply everything at once. Learning about learning is just like anything else, we start off as beginners and get better and better at it with practice and over time. The goal of this article is to walk through simple steps I took to get on the path of getting better at learning.

First, however, I’ll shed some light about how our brain learns. I’ll then share my best learning tips and finish with some personal thoughts.

How our brain learns

Researchers have found that our brain has two modes of thinking that are fundamentally different: focused and diffuse mode. Understanding them and knowing how to use both is essential to learning effectively.

Focused Mode

Focused mode, a term coined by Barbara Oakley in her book a Mind for Numbers, is the mode we all know about. It is a highly attentive state associated with the brain’s prefrontal cortex. Whenever we turn our attention to something, we’re in focused mode. It directly involves solving problems using rational, sequential, analytical approaches and it is also responsible for language processing. We can imagine this state as a CPU that processes instructions step-by-step, in order.

Examples of focused mode activities: working on a problem, programming, doing a test, reading.

Diffuse mode

The second mode, diffuse mode, is much less known and is under used for learning. It is what happens when we relax our attention and just let our mind wander. This relaxation can allow different areas of the brain to hook up and return valuable insights while we’re “thinking” of something, and this can happen possibly days later. It is critical for intuition, problem solving, and creativity. It allows us to suddenly gain a new insight on a problem we’ve been struggling with and is associated with “big-picture” perspectives. It doesn’t do any verbal processing, and that means its results aren’t verbal, either.

Unlike the focused mode, the diffuse mode seems less affiliated with any one area of the brain—we can think of it as being “diffused” throughout the brain.

How does this diffuse mode look like concretely?

Have you have ever found the solution to a problem (a bug, the name of something you couldn’t remember, a math problem) come to you while you’re doing something totally unrelated to your initial task? Or sometime the next day, when you aren’t thinking about it? That’s because diffuse mode is asynchronous. It’s running as a background process, churning through old inputs, trying to dig up the information we need.

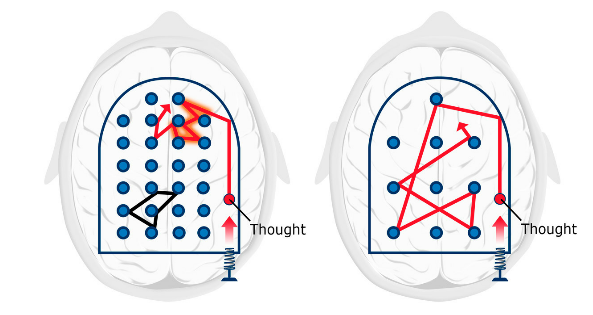

Image credit: A Mind for Numbers

These two pinball machines represent focused (left) and diffuse (right) ways of thinking. The red line represents a thought. When we focus on something, the prefrontal cortex automatically sends out signals along neural pathways. These signals link different areas of our brain related to what we’re thinking about (represented in the image as nodes).

The focused approach relates to intense concentration on a specific problem or concept. The thought is limited to how much our working memory can hold. It can sometimes be focused on thoughts that are in a different place than the “solution thoughts” actually needed to solve a problem. On the contrary, the diffuse mode doesn’t allow us to focus tightly and intently to solve a specific problem—but it can allow us to get closer to where that solution lies because we’re able to travel much farther before running into another node.

Examples of diffuse mode activities: gym, paint, shower, meditate, sleep, music, etc.

We need both for optimal learning

Problem solving in any discipline often involves an exchange between the two fundamentally different modes. Each mode contributes to our mental engine, and for best performance, we need these two modes to work together. The volleying of information between the two modes as the brain works its way toward a conscious solution appears essential for understanding and solving problems and understanding complicated concepts.

One reason for this is due to the Einstellung effect: It refers to getting stuck in solving a problem or understanding a concept as a result of becoming fixated on a flawed, initial approach. Switching modes from focused to diffuse can help free us from this effect and break that fixation. Initial ideas about problem solving can be very misleading.

The 2 modes work together, but not at the same time

This is important to know because so long as we are consciously focusing on a problem, we are blocking the diffuse mode, and stopping it from helping us solve problems.

Some of my simplest and most effective learning techniques are directly related to these two modes.

Tips for better learning

Tip #1: Taking a break from the task we’re working on

Because our brain uses two very different processes for thinking and that we toggle back and forth between these modes, it is important to focus initially, but also to turn our focus away from what we want to learn. We must consciously allow the diffuse mode to take over by simply doing something different. This could mean anything from taking a small break, going for a walk, sleeping, or working on a different problem. This is the best way to solve problems and come up with new ideas.

How you get yourself to focus away from the task at hand is up to you. A technique I like to apply this is the Pomodoro. It consists of cutting my studying / working sessions into chunks of 25 mins of focused work using a timer (I increase this to 45 mins / 1 hour if I’m coding), followed by a small break. When I’m stuck on a problem or frustrated by not finding the answer, I’ll take a longer break to allow the diffuse mode to run in the background.

When I was learning about the diffuse mode, I began to notice it in my daily life. For instance, I realized my best insights were always in the shower, when taking a walk, exercising, or when listening to music. Especially when the problem was difficult, taking a break was much more effective than when I sat down intent on trying to find out how to solve it.

Similarly, it is better to work on math or new machine learning concepts in small doses — a little every day — rather than to cram the learning within a tight period. It allows both the focused and diffuse modes the time they need to do their thing so we can understand what we’re learning. That is how solid neural structures are built.

Tip #2: Understanding the real impact of procrastination

Now that we understand how essential diffuse mode is to learning, anything preventing it from being used should be avoided at all costs. It turns out procrastination completely blocks diffuse mode. That’s because when we procrastinate, we are leaving ourselves only enough time to do superficial focused-mode learning. If we only leave a few hours or a day before completing a task, it removes the opportunity for our diffuse mode to help.

This means that procrastination doesn’t simply affect productivity, it also negatively impacts our learning. Our brain is like a muscle—it can handle only a limited amount of exercise on one subject at a time. This is why spacing our learning is so important.

Last effect of procrastination I’ll mention is that is also interferes with two essential techniques for learning efficiently: 1. Recall (as opposed to passive rereading which is usually a waste of time) and 2. Spaced repetition (great article on the subject). I won’t get into the details of how these techniques work and why they’re essential— there are already tons of resources for that— but they absolutely should be part of your learning repertoire.

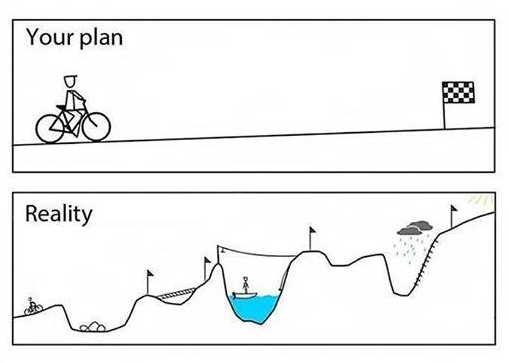

Tip #3: A random approach, without goals nor structure, tends to give random results

In previous attempts of learning new things, I have found that it’s the vagueness of my learning goals that actually killed my attempts at learning. I would simply pick a course and dive right in. This time however, I spent weeks researching and refining my own personal curriculum in machine learning, I created goals and milestones to reach, and a clear path to reaching them. This is a game changer as I have managed to learn machine learning without going to college.

Tip #4: Taking responsibility for our own learning is one of the most important things we can do

No matter how good a given teacher or textbooks is, it’s only when we sneak off and look at other resources that we begin to see that what we learn through a single teacher or book is a partial version of the full, three-dimensional reality of the subject. In the worse case scenario, the teacher and textbook are just plain bad in the first place. This is why it is important to not put all of our faith into once source, and one format of learning. This is especially important in college: it’s still worth looking at exceptional online resources even though you may have a great teacher.

Tip #5: Taking notes & using a proper note taking app

This is a classic one but so essential to becoming organized. I take three types of notes.

1. I set goals for my study (and life more broadly - as I’ve written about here). This helps keep in mind big picture perspective, objectives and why I do what I do.

2. I keep a planner-journal of daily and weekly to-do’s to make sure I’m on track with those goals.

3. I write down what learning techniques I am using, and ones I wish to try next. I then observe what does and doesn’t work, then try to iterate on these techniques and try different variations of them. This forces me to get better at learning.

I also highly recommend buying an iPad and using GoodNotes app. The app makes it substaintially better than taking notes on paper. I will 100% never go back to paper.

Tip #6: Studying with a friend

It’s easy to slack off if we’re venturing on something alone, with no one to hold us accountable. Countless times I have been in a motivational slump, only to bounce right back after a study session with a friend, or a simple conversation about what we’ve learned. Finding people you can study with is an incredibly important step especially if you’re not in college and don’t have classmates. Having people we can turn to in tough times, who know exactly what we’re going through because they are studying the exact same thing is not to be underestimated.

Personal thoughts about learning

I’ll finish this article with this important insight: learning isn’t done to you; it’s something you do.

Properly learning something new is hard and feels uncomfortable at first. It doesn’t work to just sit there and passively watch a bunch of YouTube videos or read a few articles (something I was a victim of). That would be too easy. To get real results we need to be consistent, committed and learn actively. Learning actively means really engaging in the material we’re studying: solving practice problems, recalling study material, testing ourselves (flash cards are your friend), explaining to others a concept we just learned, etc.

This is also one of the reasons why companies that buy the standardized 1 day / 1 week training courses don’t work. They’re popular because they’re easy to purchase, it’s easy to schedule, and managers can pat themselves on the back thinking they’re investing in their employees. But if we’re not taking advantage of how our brain learns, and other techniques mentioned above, the result will be subpar.

Reshaping our brain is under our control. The key is patient persistence: working knowledgeably with our brain’s strengths and weaknesses. By understanding our brain’s default settings— the natural way it learns and thinks— we can take advantage of this knowledge to become an expert at anything.